Jackie Hahn

About the Exhibition

I have always been attracted to politics, of community and of identity. As a queer, asian, non-binary teenager living in the world of late-stage capitalism with an ongoing climate crisis, my identity has always been one of conflict. I am fascinated by the labels that have not just given names to my experience, but also its rather potent influence on my life. I see this in my own work in “boxing”, “queer”, and “nude.” My experiences of discrimination and prejudice inspire me to find myself in my own work, and to create my own imagery divorced from the narratives that have built oppression against people like me.

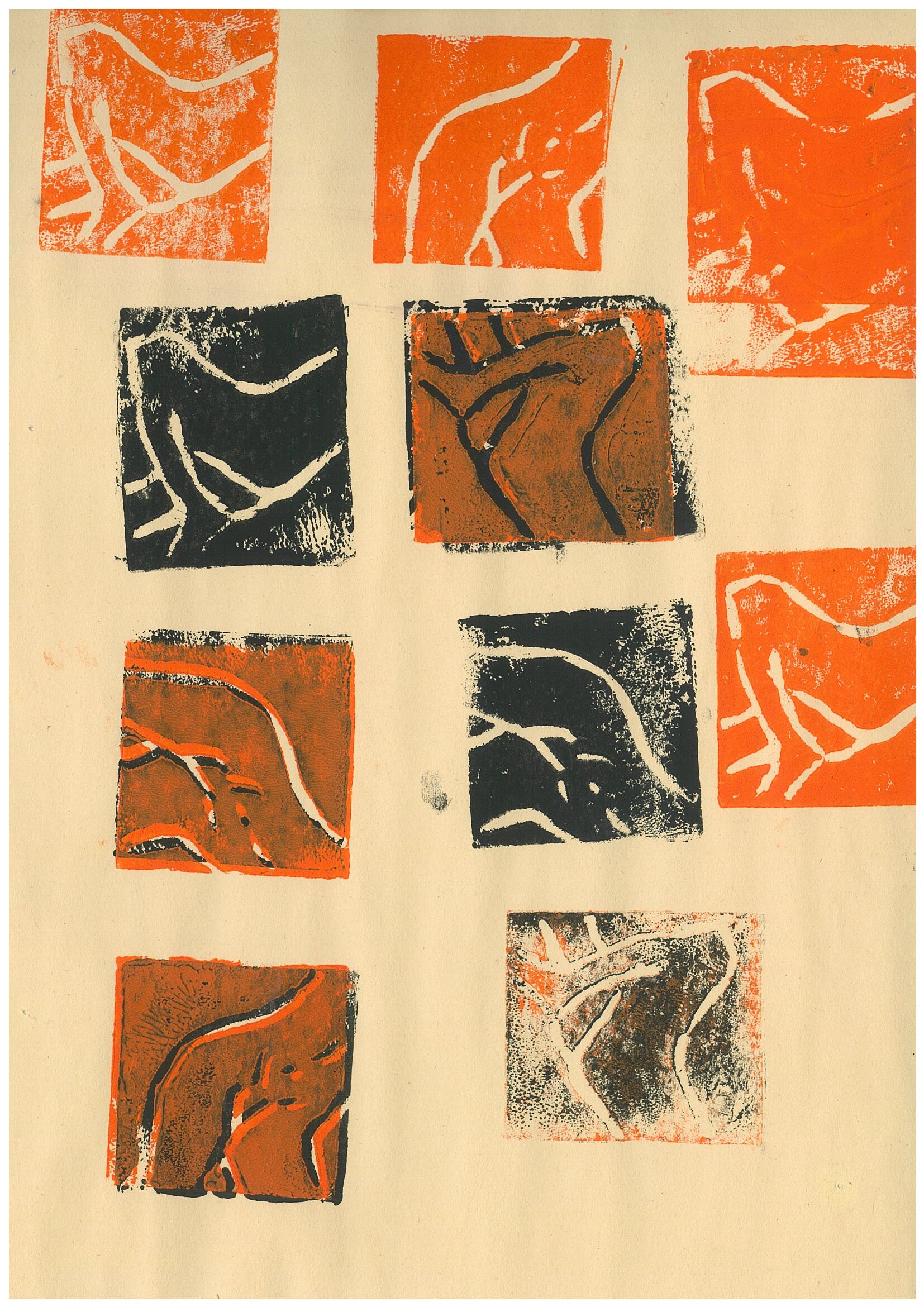

The linocut has a history of being involved in activist artwork from artists like Kathe Kollwitz to more modern artists and communities such as the Queer Ancestors Project and Favianna Rodriguez. As a cheap and easily accessible medium that is also reproducible, the linocut has been a popular medium for activists looking to spread imagery and information related to their cause. Koreans generally associate this form with their childhood, as many of them did linocuts in elementary school, and so I believe it also has a level of childlike possibility within it. The context of western activism and the korean connotation of childhood imagination allow me to create work in both contexts.

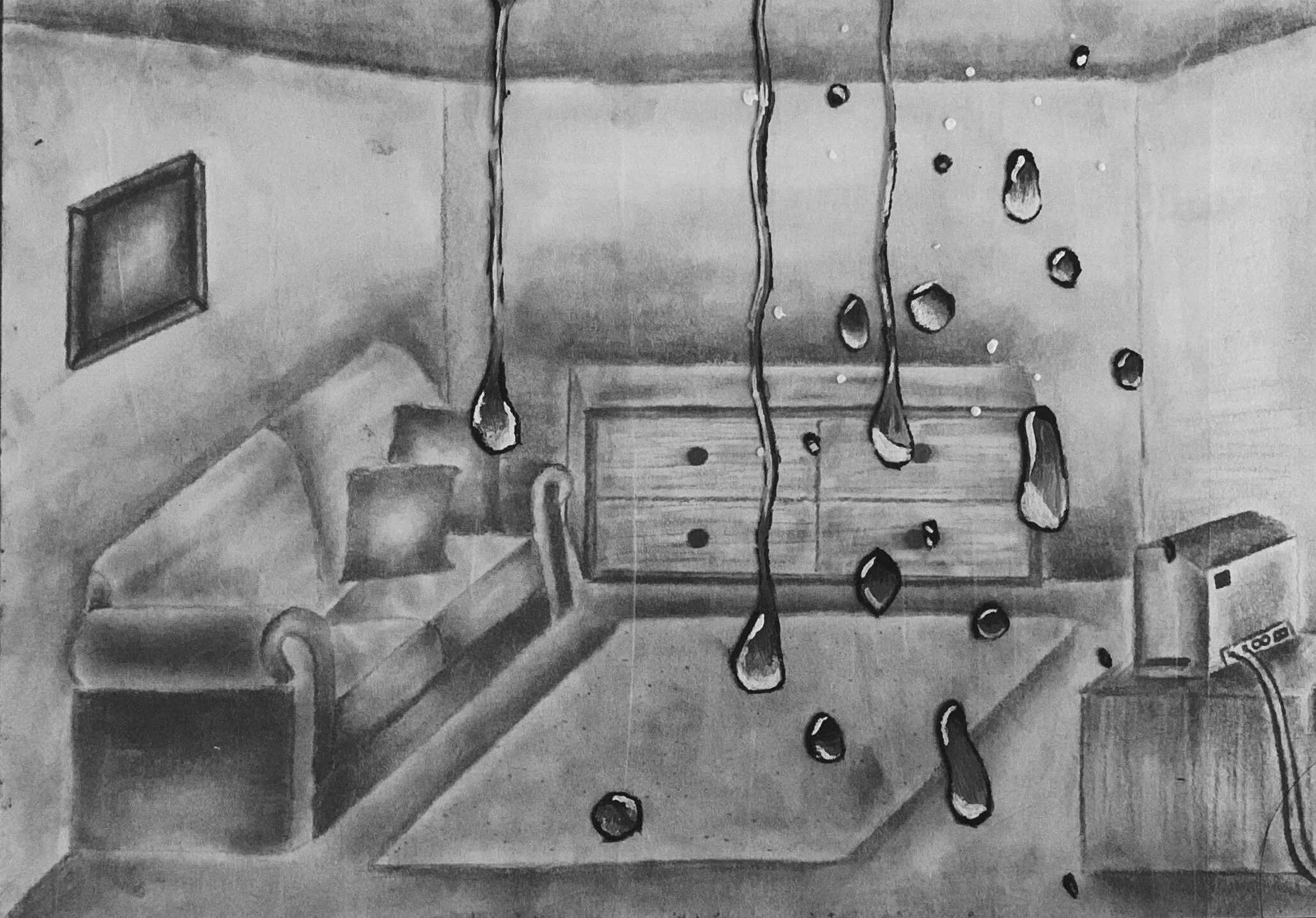

I felt these works should flood the audience. I saw that the warm color of the manila paper gave a warm, inviting feeling, but also the contradictory feeling of being overwhelmed. The dual effect further complicated the space, which I rather found fascinating and the free exhibition seemed much more appealing to me than the isolated, confining display of a frame in traditional exhibition space. The effect of warmth could be furthered by an emphasis on a communal space, with a wide variety of lights to emphasize a collective effort. Strings across the top of the exhibition area from which lights and artworks could hang, would bring out a makeshift feeling and the act of looking up (a symbol of hope). The addition of books and a wooden stool to immerse oneself in the space, would have added to an overall feeling of an invitation.

The opposite side is literally, the other side. Audre Lorde particularly inspired this train of thought in how she critiqued forms of storytelling for being made for the white man. Minority populations, stories that conflict with the white man’s narrative are not meant to be appropriated to fit such narratives. For Lorde this meant breaking down language to create, to some extent, a new language more fitting to her experience. For me, this meant a space where work is produced and looked at collectively. In particular, I built this off of my experience of a Keith Haring exhibition. The works - despite championing gay rights, safe sex and playful, crude imagery- felt cold. They were framed and set apart, often in white large spaces. There was something uniquely wrong about the whole situation, and instead of inviting me (queer, asian) to interact with work about my own history, it alienated me.

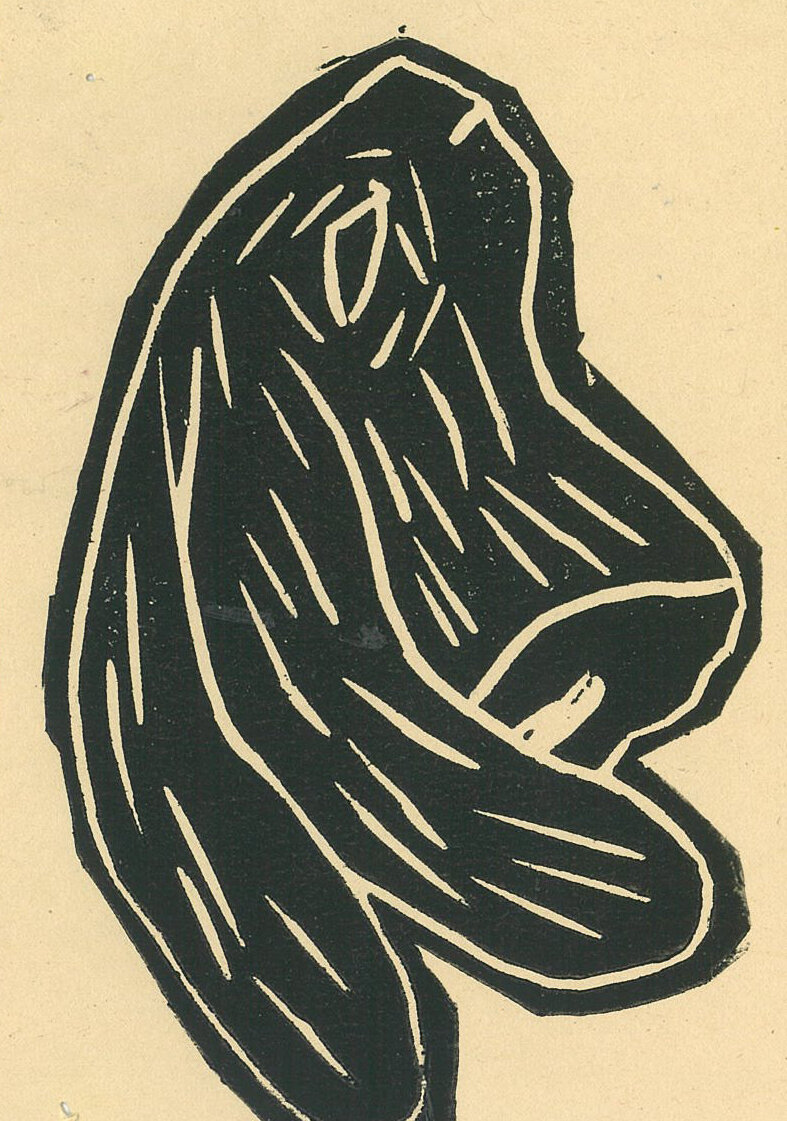

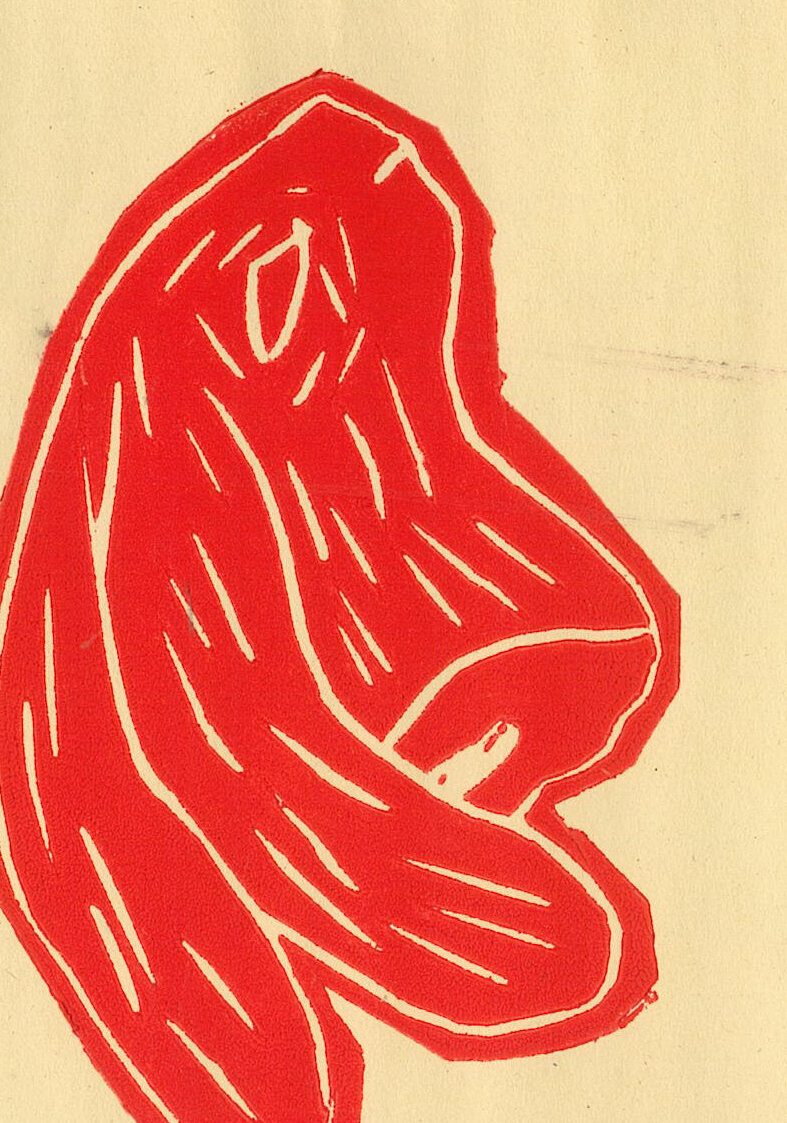

The other side would have work that fights against capitalism, critiques racism or gender discrimination. “Enby” is a work that is deeply personal to me, it means non-binary in modern day slang, and depicts a struggle against gender and performativity. To have a work so personal splayed on a white background, under harsh light, alone and separated, caged in a frame is (for me) the wrong way to exhibit the work. For this part of the exhibition, it was the right, wrong way. The same goes for the other two works. Protest signs splayed like a frog and the fight against the inherent bias of the American police force sponsored by big corporations and billionaires in support of it.

The back to back of the two spaces would enhance each other’s effects, the collective exhibition more inviting, more warm and the other side colder, more ironic. The overall effect of the exhibition would be a challenge towards traditional exhibition spaces, about the lost voices of minority artists in a capitalist society where sometimes, artistic labor is sold to survive while billionaires get richer on tax cuts.